Travel

How to claim asylum in the UK

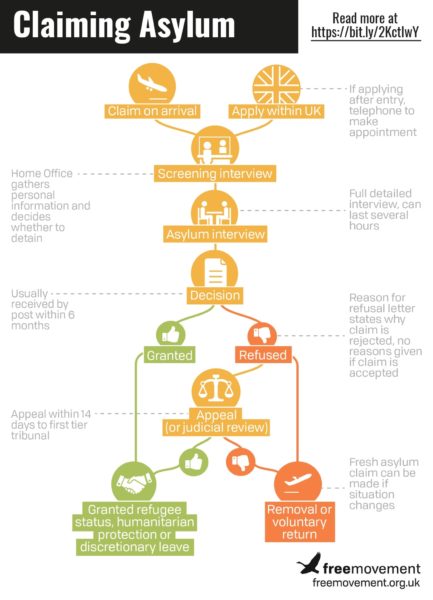

Claiming asylum is an important human right backed by the United Nations Refugee Convention and recognised by countries around the world.

In order to make this right a reality in practice, countries like the UK have set up systems by which people must apply for asylum. In this way, asylum seekers who are considered to meet the criteria for refugee status are separated from those who, in the view of government officials called decision makers, do not qualify. In the United Kingdom, this is done by the Home Office, a government department.

This article aims to gives readers a basic understanding of the process of claiming asylum. It is drawn from the Free Movement online training course Introduction to the UK asylum process, which expands on this article and includes worked examples.

Lodging the claim

A person can claim asylum provided that the claim is made at a “designated place”. A “designated place” is defined exhaustively in section 14 of the Nationality and Borders Act 2022, and includes at a port of entry (for example, an airport or port), at an Asylum Intake Unit and in a removal centre.

Claiming asylum at the port of entry means, in practice, informing a Border Force officer of an intention to seek asylum. Border Force officers will usually be wearing blue uniforms with “Border Force” written on them. In practice, the border officers that people will encounter are those doing passport controls at the airport or port. One should simply let them know that they are afraid of returning to their country and want to claim asylum in the UK.

When claiming asylum at the port of entry, individuals will usually be immediately asked questions about their claim, in the form of a “screening interview”. If the screening interview does not take place on the same day, it would usually take place within five days.

If wishing to claim asylum after they have entered the UK, people must start by calling the Home Office to book an appointment at the Asylum Intake Unit.

Throughout the process of claiming asylum, individuals or their legal representatives can email the Asylum Central Communications Hub with queries, requests, supporting documents and other updates such as changes of address. The Home Office has published guidance on how to email the Asylum Central Communications Hub, including email templates to ensure that the correct information is provided.

Interview

Screening interview

Screening interviews usually take place at Lunar House, in Croydon. Those who claim asylum in Northern Ireland will be invited to attend Drumkeen House, in Belfast. There is little privacy at Lunar House: the waiting area is open plan, and rooms where interviews take place are often only separated by a glass screen. It is sometimes possible to hear what happens in the next room.

Where possible, claimants should attend their screening interview with evidence of identity (including their passport) and evidence of their accommodation in the UK (for example, a recent bank statement or utility bill, or a letter from the landlord). Claimants may also be told by the Home Office to attend the screening interview with evidence in support of their claim.

At the screening interview, the Home Office will take claimants’ “biometric information”: that is, their fingerprints and photograph. The biometric information is used to verify the claimant’s identity, and also to issue their ARC (Application Registration Card).

Here is the Home Office form used at a typical screening interview, showing the questions that will be asked.

Interview under caution

Under section 24 of the Immigration Act 1971 (as amended by section 40 of the Nationality and Borders Act 2022) it is a criminal offence to knowingly enter or arrive in the UK without leave to enter.

This means that people arriving by small boat or hidden in lorries without a visa to the UK will be committing a criminal offence. Where a person is suspected of committing a criminal offence they may be interviewed under caution.

Being declared an illegal entrant does not have an immediate impact on the asylum claim. If the claimant meets the definition of a refugee, they will still be granted status.

But it might affect their immigration status in the future, including in an application for British citizenship; a recent update to the guidance on the ‘good character requirement’ states:

Any person applying for citizenship from 10 February 2025, who previously entered the UK illegally will normally be refused, regardless of the time that has passed since the illegal entry took place.

At the end of the screening interview, claimants will be given a copy of their screening records. These are written records of what they said during the interview. They will not be given copies of the records of the interview under caution, if that took place.

Claimants will also usually be issued with a Section 120 One Stop Notice, on the day or by post after the screening interview. The One Stop Notice will look something like this.

At the interview, the claimant will need to hand over their passport (if it is not already with the Home Office) and, if they have one, their Biometric Residence Permit. Claimants will be sent an Application Registration Card (ARC) instead, which will be their form of identity until the claim terminates.

Inadmissability

Where it is known or suspected that a claimant travelled through safe third countries on their way to the UK, the case will be referred to the Home Office’s Third Country Unit. This Unit considers whether the claim should be certified as inadmissible. If a claim is certified, the Home Office is not required to consider the claimant’s asylum claim and can remove them to a safe third country.

Once the Home Office’s Third Country Unit has reviewed the case, it will decide if it is admissible or not. If the case is inadmissible, a notice of intent will be issued to the claimant. A notice of intent is a letter explaining that the claimant’s case is being considered for inadmissibility, the reasons why and what safe third country or countries the Home Office is considering return to. The notice will state a deadline for any response. In practice, this is usually 14 days.

When formulating a response to a notice of intent, legal representatives should consider the claimant’s individual characteristics and vulnerabilities and take detailed instructions regarding their journey to the UK. They should also consider objective evidence on the countries the Home Office has indicated they consider are safe to return to. There may be a need for medical evidence. Where more time is needed to gather evidence, timely requests for an extension of time should be made.

The Home Office’s caseworker guidance on inadmissibility states:

There are no rigid timescales within which third countries must agree to admit a person before removal. However, the inadmissibility process must not create a lengthy ‘limbo’ position, where a pending decision or delays in removal after a decision mean that a claimant cannot advance their asylum claim either in the UK or in a safe third country. If, taking into account all the circumstances, it is not possible to make an inadmissibility decision or effect removal following an inadmissibility decision within a reasonable period, inadmissibility action must be discontinued, and the person’s claim must be substantively considered.

As a general guideline, it is expected that in most cases, a safe third country will agree to admit a person within 6 months of the claim being recorded, enabling removal soon after, subject to concluding legal challenges or other removal barriers.

There will be some cases where a reasonable timescale may be shorter than 6 months, because there are not realistic prospects of effecting removal within a reasonable timescale. For example:

– where there is no prospect of removal, because all possible countries of removal have emphatically refused to accept the person

– where there is a very low prospect of removal within a reasonable timescale, because the countries of removal refuse to engage in any discussions around admitting the personIn other cases, what is reasonable may be longer than 6 months. For example:

– if early inadmissibility processing has been delayed, because a claimant’s presence in or connection to a safe country was not disclosed or clearly evidenced at the time the asylum claim was made and registered, but instead is disclosed at a later time, for instance, during an asylum interview

– if a person whose age is initially disputed is treated as a child and therefore not progressed in the inadmissibility process, but is later assessed to be an adult

– where third countries have actively engaged with the Home Office in discussions around admitting a person (or people), but where through no fault of the Home Office, progress towards agreement has been delayed

– where a claimant is referred into the National Referral Mechanism, it will be usually be appropriate to pause inadmissibility action until the consideration of whether or not the person is a victim of modern slavery has been completed

Where inadmissibility action has been triggered, the claimant’s asylum claim will not be progressed until it is referred out of the Home Office’s Third Country Unit. There is no appeal right if the claim is certified as inadmissible. The only remedy is judicial review.

Substantive interview

If the asylum claim is admissible, asylum claimants or their representatives will then receive a letter with the date, time and place of the substantive interview. This is what the letter might look like.

The substantive interview involves questions about what happened to the claimant in the past, when, where, with whom etc. Interviewers will generally ask questions about documents which were submitted beforehand, to check that what the claimant says is consistent with the documents. When an inconsistency arises, interviewers should give the claimant an opportunity to explain it. In practice, when the Home Office is minded to refuse, inconsistencies will still be used to refuse claims even when explained.

The interview is likely to take place via video conferencing. The claimant will still be required to travel to a Home Office venue for the interview where they will sit in a private room on their own or with their legal representative. The interviewer and interpreter will join via video link.

Depending on the claimant’s individual circumstances, video conferencing may not be appropriate. In these cases, the claimant’s legal representative’s can provide submissions why a face to face interview is required with reference to the Home Office’s policy.

Interviews may last anywhere between one hour and six to seven hours (occasionally even longer), although the average length is about four hours. The interviewer will often schedule breaks every one or two hours. It is also possible for the claimant to ask for breaks if needed.

This may be worth doing, as the interview process can be exhausting, with hundreds of questions asked. If a claimant starts feeling tired, confused, or upset, they should ask to take a break to start afresh rather than “powering through” and starting to get answers wrong.

Legal representatives are allowed to attend the interview but they may not interrupt unless to draw attention to a serious misunderstanding between their client and the interviewer.

A claimant also has the right to ask for an interpreter to assist during the interview. A claimant who needs an interpreter will usually have asked for it when they first claimed asylum, either at the port of entry or when calling the Home Office to book a screening interview. During that call, one of the questions the Home Office will ask is whether the claimant needs an interpreter. If a claimant says that they need an interpreter, an interpreter will be provided both at the screening interview and at the substantive interview.

During the interview, the interviewer will be transcribing the questions and answers given at the interview. These can be hand-written notes although most interviews are typed these days. At the end of the substantive interview, claimants are given a copy of these written records.

It is Home Office policy to record asylum interviews, unless the claimant requests to not be recorded. The example given in the policy of why a claimant may not wish to be recorded is where the claimant is a victim of torture and the torture involved the recording of their abuse.

If the audio recording equipment fails during the interview, the interviewer must seek the claimant’s consent for the interview to proceed without being audio recorded. They also must offer to delay the start of the interview so that the claimant can seek legal advice.

After the substantive interview

It is very important for claimants and their legal representatives to review the written records shortly after the interview. They will usually have five working days to make any comments on the records (for example, if some answers were not transcribed accurately or the claimant made a mistake that they want to rectify).

If the Home Office is minded to refuse, it will often do so by relying on mistakes which might have been rectified. The fact that they were rectified earlier on boosts the credibility of the claimant at the appeal stage. The case of MM (unfairness; E & R) Sudan [2014] UKUT 105 (IAC), discussed in this blog post, underscores the procedural importance of writing to the Home Office to correct the record.

In those five working days, the claimant and their legal representatives can also submit any new evidence they may have in support of the claim. Submissions can be made via email to the Asylum Central Communications Hub. This is important because new matters which were not deemed to be important to the claimant might have arisen during the interview, and might need to be corroborated to boost the claimant’s credibility.

If inconsistencies have arisen during the interview, and those inconsistencies may be “corrected” by submitting further evidence, that should also be encouraged.

If the claim is successful

Next steps

If the claim is accepted, an asylum seeker will generally be granted five years’ refugee status.

Refugees will be sent their decision via email or post. Claimant’s may need to request that their original documents are returned to them.

Successful asylum applicants are allowed to live, work and study in the UK, and access public funds. Information about claiming benefits is available from the Department for Work and Pensions and the charity Citizens’ Advice.

There is an integration loan available for those who have refugee status, humanitarian protection, or are a dependent family member of someone with refugee status or humanitarian protection. The loan is available to pay for things such as rent, basic living costs or education and training for work. Those applying alone can borrow between £100 and £500, and those applying with a partner can borrow between £100 and £780. The loans are interest-free, so long as regular repayments are made.

Refugees may also apply for family reunion for family members, as set out in Appendix Family Reunion (Protection) of the Immigration Rules. More details are available in the Free Movement training course on family reunion.

A successful refugee will have a UK Visas and Immigration account set up where they can access online evidence of their immigration status via an eVisa. Through this account, refugees can get a share code to give to employers, landlords, banks and local authorities to demonstrate their status in the UK.

However, to travel, refugees will need to obtain Travel Documents by applying online. A refugee should not use their national passport, as that might be seen by the Home Office as “re-availing themselves of the protection of their country of origin”, which is a ground for revocation of refugee status. For more information on this see the Home Office guidance here.

Different types of status

An asylum claimant may be granted some leave which is not refugee status. In particular, it is possible to be granted:

- humanitarian protection, when a claimant does not qualify for protection under the Refugee Convention (if they will not be persecuted because of a “Convention reason”) but are still in need of international protection. For example, there might be a risk of serious harm if they return to their country of origin.

- leave under the Immigration Rules, for example on human rights grounds, on the basis that they have a partner in the UK or there would be “very significant difficulties to their reintegration in their country of origin” (under paragraph PL 5.1. of Appendix Private Life).

- limited leave to remain outside of the rules until the applicant is 17.5 years old. This is typically granted to unaccompanied minors.

- restricted leave for those who are excluded from the Refugee Convention, for example because they are war criminals, but removing them would breach their rights under Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights.

- discretionary leave for those who have a very serious medical condition which could not be treated in their country of origin.

If the claim is refused

Appealing to the First-tier Tribunal

When an asylum claim is refused there is usually a right of appeal and the appeal can usually be pursued from within the UK.

Whether or not there is a right of appeal to a judge in the First-tier Tribunal is determined by law. Specifically, section 82 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002 as amended says that there is a right of appeal in certain specific circumstances. For asylum claims, this is when “the Secretary of State has decided to refuse a protection claim made by P”, where “P” is the asylum seeker. A protection claim is defined in the section as a claim by the person that his or her removal from the UK would breach the Refugee Convention or the European Convention on Human Rights.

Where the Home Office has considered and refused an asylum seeker’s asylum claim, this will almost always give rise to a right of appeal.

Can the appeal be pursued from inside the UK?

Most asylum appeals can be pursued from within the UK. However, the Home Office can use a legal procedure called “certification” to prevent the asylum seeker from lodging an appeal until after they have been removed from the UK.

“Certification” is where the Home Office decides that an asylum claim is clearly unfounded. The law on certification is set out at section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002 as amended. Where a refusal is also certified under section 94, the refusal will say so.

If the asylum seeker wants to argue that they should be allowed to remain in the UK to pursue an appeal, they will need to lodge an application for judicial review with the Upper Tribunal. This is a different legal process to an appeal.

There have been some examples of supposedly “clearly unfounded” cases which were certified by the Home Office, resulting in the asylum seeker being removed but subsequently managing to lodge a successful appeal from abroad.

The time limit for lodging an appeal is 14 days from the date of the decision. It is extremely important to get an appeal lodged within this time limit.

It is possible for the tribunal to accept late notices of appeal. However, this is unusual and the tribunal will not usually accept reasons such as “I did not know there was a time limit” or “I do not speak English”. Where a notice of appeal is lodged late, an application to extend time must be included, very good reasons must be given and evidence to support those reasons should be enclosed.

If the claimant is represented then their legal representative should submit the appeal online using the MyHMCTS service. If the claimant is detained in prison, the appeal should be made on the paper form, IAFT-5. If the claimant is detained in an immigration detention centre, appeal by completing and sending paper form IAFT-DIA.

If the claimant does not have a legal representative they can appeal online here. Alternatively, if they cannot access the online service they can complete form IAFT-5.

Appellants can chose to have an oral hearing or a paper hearing. In an oral hearing, appellants will appear in front of a tribunal judge and give evidence, as explained in the next unit. A paper hearing, as its name indicates, will be decided by a judge having sight of the papers only. In asylum cases it would almost always be better to have an oral hearing.

The fee to lodge an appeal is £140 for an oral hearing and £80 for a paper hearing. Those who are in receipt of asylum support or legal aid do not have to pay those fees.

Appeals after the First-tier Tribunal

If an appeal to the First-tier Tribunal is dismissed, a further appeal to the Upper Tribunal can be attempted. Any further appeal needs permission to proceed, however, and can only be based on what is called an “error of law”. An error of law is some sort of legal error or mistake made by the judge. Simply disagreeing with or not liking the outcome is not an error of law.

The stages of appeal go to these tribunals or courts:

- First-tier Tribunal

- Upper Tribunal

- Court of Appeal

- Supreme Court

At each stage, an application for permission to appeal against the decision of the judge can be made at the level of the tribunal or court that made the decision and then, if that fails, to the next level up.

Fresh claims

If an asylum claim is certified, or has been refused and all appeal rights were exhausted, then a claimant may make further submissions. Once further submissions are submitted, the Home Office will need to decide whether they constitute a “fresh claim”.

The definition of a fresh claim is found at paragraph 353 of the Immigration Rules. Accordingly,

The submissions will amount to a fresh claim if they are significantly different from the material that has previously been considered. The submissions will only be significantly different if the content:

1. had not already been considered; and

2. taken together with the previously considered material, created a realistic prospect of success, notwithstanding its rejection. This paragraph does not apply to claims made overseas.

Once further submissions have been submitted, the Home Office may:

- decide that the new evidence is a fresh claim, and grant refugee status, humanitarian protection or some other type of leave; or

- decide that the new evidence is a fresh claim but the claimant is not in need of protection and refuge leave. If so, a claimant will be given a right of appeal; or

- decide that the new evidence does not constitute a fresh claim and refuse the application without a right of appeal.

If further submissions are not accepted as a fresh claim, a claimant may judicially review the decision.

This article was originally published in 2018 and has been updated by Rachel Whickman so that it is correct as of the new date of publication shown.

Related posts: