Education

What is the refugee definition in international and UK law?

[ad_1]

Lawyers do not own the word “refugee”. The term has been in use since the eighteenth century and has its own evocative, wider meaning in the public consciousness. Those fleeing Ukraine or relocating to the United Kingdom from Hong Kong can validly be referred to as “refugees”, for example, even if they are not formally recognised as refugees, might not even qualify for refugee status and might not describe themselves as refugees.

Before we get to that, we have loads of content about refugees and asylum on our website. The best place to see what we’ve got is to take a look at our Asylum Hub page. There you can find our refugee law starter pack, our collection of articles addressing various asylum myths, our 60 second explainer videos, our most recent articles about trafficking, links to important Home Office policy documents about asylum, signposts to top organisations and charities working with refugees and much more.

We are planning some other refugee-related content for you over the next week as well, including an updated briefing on the state of the United Kingdom’s asylum system, a refresh of our post on the difference between an “asylum seeker” and a “refugee” and a new post on the higher standard of proof under the Nationality and Borders Act 2022.

If you are interested in refugee issues, you can sign up to our refugee and asylum newsletter here. As soon as we publish something on refugee or asylum law, we’ll send you an email about it. You can also optionally sign up for our main weekly newsletter and, if you want to, one of our other newsletters providing instant updates on some other selected immigration law topics.

If you are really interested in refugee law, take a look at my textbook on Refugee Law, published with Bristol University Press. It was reviewed in the International Journal of Refugee Law and I’m pleased and relieved to tell it was a positive one…

What is the Refugee Convention?

The full title of the Refugee Convention is the 1951 UN Convention on the Status of Refugees. The original Convention is today usually read with the 1967 New York Protocol. When lawyers refer to “the Refugee Convention” we are usually using that as shorthand for the 1951 Convention and 1967 Protocol together.

The Convention was passed by a special United Nations conference on 28 July 1951 and entered into force on 22 April 1954. It was initially backward looking, in the sense that it was limited to protecting those who became refugees due to events occurring before 1 January 1951. The 1967 Protocol gave the Convention new life, making it a living, forward looking instrument that offered protection on an ongoing basis.

You can read about the history of the Refugee Convention and its full text on the UNHCR website here.

Not all countries have signed up to both the original 1951 convention and the 1967 protocol and some have retained the optional geographical limitations which were permitted when the Refugee Convention was first created. Turkey, which in 2021 hosted some 4 million refugees, has ratified both the convention and protocol but maintains a geographical limitation to “events in Europe”, with the effect that Turkey is therefore under no international law obligation to offer those refugees the rights set out in the convention.

What is the legal definition of a “refugee”?

The legal definition of the term “refugee” is set out at Article 1A(2) of the Refugee Convention, which defines a refugee as a person who:

owing to well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion is outside the country of his nationality and is unable or owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country; or who, not having a nationality and being outside the country of his former habitual residence is unable or, owing to such fear, unwilling to return to it.

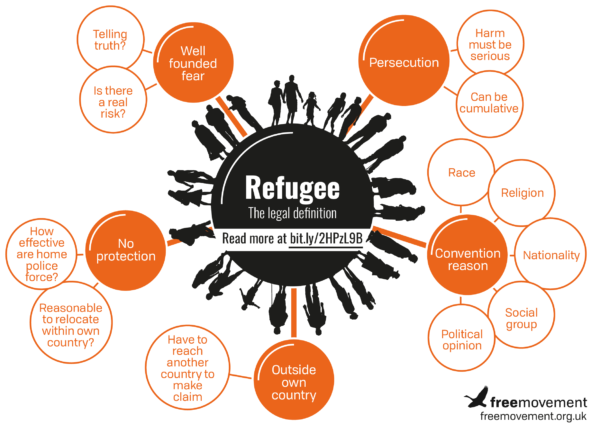

The definition can be broken into constituent parts:

- Possession of a fear that is well founded rather than fanciful

- Of treatment that is so bad it amounts to being persecuted

- For one of five reasons, referred to as ‘Convention reasons’: race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion

- Being outside one’s country

- Being unable or unwilling to obtain protection in that country

All of the conditions need to be met for the person to be considered a refugee. For example, a person might have a well founded fear and be unable to get protection but if that person does not fear being persecuted for a Convention reason then the person is not a refugee in legal terms. Another person may meet all the other criteria for refugee status but be living in a refugee camp in their own country, in which case he or she is not a refugee and instead would often be referred to as an Internally Displaced Person.

In casual conversation or in the media the word “refugee” is often used to refer to people fleeing civil war, disaster, famine or conflict. There is nothing wrong with calling them refugees, but they do not necessarily meet the legal definition of a refugee in the Refugee Convention. Even victims of civil war do not always qualify for refugee status, if for example they are considered not to have been targeted by either side in the conflict but to have fled the general security situation.

Want all this explained in just 60 seconds? Check out our video on the Refugee Convention:

Want it all explaining in boring old written words? Read on…

What does “well founded fear” mean?

There are two dimensions to “well-founded fear” under the Refugee Convention:

- The refugee must generally show that he or she is telling the truth. If the whole account of what happened is false then usually (but not always) there will be no well founded fear if the person is returned.

- The level of risk of something bad happening if the refugee is returned must be more than fanciful, otherwise it is not “well founded.”

Lawyers and judges in the UK have historically, since the landmark House of Lords case of ex p Sivakumaran [1988] AC 958, used a standard of proof which is more generous than the normal civil standard of the balance of probabilities. With the balance of probabilities, a person must show that something is more likely than not, or that there is at least a 51% chance of it happening.

In refugee cases the standard of proof is expressed as “reasonable degree of likelihood” or “real risk”. This standard was being applied both to assessing whether the refugee is telling the truth and what the chances of something bad happening are in the future. Now that section 32 of the Nationality and Borders Act 2022 has come into effect for asylum claims made on or after 28 June 2022, a more complex split standard of proof will apply. The civil standard will apply to assessment of the refugee’s personal characteristics and past events and the real risk standard will apply to assessment of future risk of harm. We have another post looking at this change in more detail coming out later this week.

What does “persecution” mean?

The meaning of “being persecuted” is not defined in the Refugee Convention itself. This is deliberate: it allows the meaning of the word to be flexible and to evolve over time. This is useful for refugee protection purposes, but it does mean that the student of refugee law will need to look to various other sources and reference points in order to understand the contemporary meaning of the word and how it has evolved. These sources include the views of UNHCR (the office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees) and refugee law academics, other relevant international legal instruments and the domestic and international courts.

The respected UNHCR Handbook begins its description of persecution at paragraph 55:

There is no universally accepted definition of “persecution”, and various attempts to formulate such a definition have met with little success. From Article 33 of the 1951 Convention, it may be inferred that a threat to life or freedom on account of race, religion, nationality, political opinion or membership of a particular social group is always persecution. Other serious violations of human rights — for the same reasons — would also constitute persecution.

The courts have been wary of giving specific guidance on the level of ill-treatment required before that ill-treatment can be described as ‘being persecuted’. The reason for this apparent vagueness is simply that the most judges realise that rigid guidance is inappropriate. As Guy Goodwin-Gill wrote in the classic second edition of The Refugee in International Law (Oxford, 1996):

There being no limits to the perverse side of human imagination, little purpose is served by attempting to list all known measures of persecution. Assessments must be made from case to case by talking account, on the one hand, of the notion of individual integrity and human dignity and, on the other, of the manner and degree to which they stand to be injured.

Some guidance has emerged over time as to the level of seriousness the treatment must attain. In the influential landmark House of Lords case of Shah and Islam [1999] INLR 144 Lord Hoffman famously adopted the formula

Persecution = Serious Harm + The Failure of State Protection

The issue of state protection is examined in more detail below, but “serious harm” is as close as the UK courts have come to offering a working and readily intelligible definition of the high threshold for persecution.

Here in the UK, the Nationality and Borders Act 2022 defines persecution at section 31. Persecution must be sufficiently serious by its nature or repetition as to constitute a severe violation of a basic human right or can be an accumulation of various measures that affect an individual in a comparable way. This might, for example, include an act of physical or mental violence, including sexual violence, legal, administrative, police or judicial discriminatory measures, prosecution or punishment which is disproportionate or discriminatory or other measures.

How important are the Refugee Convention reasons?

The five Convention reasons — race, religion, nationality, social group and political opinion — are very important because without showing that the future risk is because of one of these reasons, a claim to refugee status will fail.

This means that some people commonly referred to as refugees are not formally refugees within the legal meaning of the Refugee Convention. For example, people who flee their homes due to famine or flooding or environmental disaster do not fear persecution for any of the Convention reasons.

Most of the Convention reasons are fairly self-explanatory. We all know roughly what is meant by race, religion, nationality and political opinion. Some further explanation and definition can be found in the Nationality and Borders Act 2022 and in case law but these words are mainly interpreted within their ordinary meaning.

The Convention reason most open to interpretation is “membership of a particular social group”.

There is some legal consensus on what it does not mean:

- The definition should not be so wide that it renders the other Convention reasons redundant: it is not some sort of “catch all” category.

- The members need not be homogenous, cohesive or small in number.

- It is not necessary to show that all members of the particular social group are persecuted.

There is also legal consensus on what it does mean.

- The particular social group must exist independently of the persecution suffered; if persecution alone created a particular social group then there would be no need for any other Convention reason, rendering them otiose.

- The meaning should be “of a kind” with the other Convention reasons.

- Members of that group share an innate characteristic, or a common background that cannot be changed, or share a characteristic or belief that is so fundamental to identity or conscience that a person should not be forced to renounce it.

Section 33 of the Nationality and Borders Act 2022 adds an additional condition: that the social group “has a distinct identity in the relevant country because it is perceived as being different by the surrounding society.” This was previously considered an alternative way of identifying a particular social group rather than an additional requirement, which raises the concern that the change makes it harder for some people to qualify as members of a particular social group.

Example

Women have been held to be a particular social group where there is evidence of systematic State discrimination against women: Shah and Islam [1999] 2 AC 629.

Females at risk of Female Genital Mutilation were held to be members of a particular social group in K and Fornah [2006] UKHL 46.

Being a member of a family was also held to be capable of being a member of a particular social group in K and Fornah [2006] UKHL 46, even where the persecution directed against the family originally arose for reasons other than under the Convention. This brings a victim of a blood feud potentially within the scope of the Convention, for example.

Gay men and women were held to be capable of constituting a particular social group in HJ (Iran) [2010] UKSC 31 where there is evidence of discrimination.

In SM (PSG, Protection Regulations, Regulation 6) Moldova CG [2008] UKAIT 00002 the Tribunal found that “former victims of trafficking” and “former victims of trafficking for sexual exploitation” are capable of being members of a particular social group because of their shared common background or past experience of having been trafficked.

What level of failure of protection is needed?

The Refugee Convention has been described as offering “surrogate international protection”, meaning that where a person’s own state persecutes or fails to protect them, they are entitled under international law to seek protection elsewhere. Where a person faces persecution, no protection is available and they cannot reasonably be expected to relocate elsewhere in their home country, they will qualify as a refugee.

Where a state is persecuting a person, the issue of protection does not really arise. The police are unlikely to offer protection and may indeed be actors of persecution themselves. It is unlikely in a state persecution case that the victim will be able to find anywhere safe in the country concerned.

Where the persecution comes from private individuals or non state actors, such as a political organisation, a faction in a civil war or a terrorist organisation, the issues of state protection and internal relocation become more relevant.

In a case called Horvath [2000] UKHL 37 the House of Lords held that the test is whether the system of protection is one which is generally effective as opposed to one which guarantees prevention of harm for the person seeking asylum. This was a controversial decision and it can mean that an asylum seeker is sent back to a country of origin even though there is a well founded fear of serious harm.

The Horvath decision is now codified in section 34 of the Nationality and Borders Act 2022, which states that protection must be considered to be available where the state or an entity controlling the state or a substantial part of territory “takes reasonable steps to prevent the persecution by operating an effective legal system for the detection, prosecution and punishment of acts constituting persecution” and the person seeking asylum is able to access that protection.

Section 35 of the Nationality and Borders Act 2022 states that a person cannot qualify for refugee status if they can reasonably be expected to travel to and remain in that part of the country. The meaning of “reasonable” is not elucidated any further in the legislation itself.

This test for whether it is reasonable to expect a person seeking asylum to go back to their home country and live somewhere else (“internal relocation”) was considered by the House of Lords in two cases in fairly quick succession, Januzi [2006] 2 AC 426 and AH (Sudan) [2008] AC 678. These cases unhelpfully answer the question of when an asylum seeker might reasonably be expected to relocate by posing a new question: would it be ‘unduly harsh’? Case law makes it clear that this is a high test, though: can the person lead a relatively normal life — judged by the standard of their home country — without facing undue hardship?

What else is in the Refugee Convention?

As well as the definition of a refugee at Article 1A(2), the Refugee Convention includes articles dealing specifically with Palestinian refugees, loss of refugee status, exclusion from refugee status and the rights of refugees. If you want to know more, check out our Asylum Hub or buy my refugee law book. As well as taking readers through the Refugee Convention itself it includes chapters on the wider international law framework, the history and evolution of refugee law, outlines the fundamental features of the UK asylum system and looks to the future of refugee law and protection.

What is the difference between a refugee and an asylum seeker?

Later this week we will publish an updated blog post looking at this question so we’ll keep it short here.

An asylum seeker is an informal term used to describe someone who is seeking asylum but has not yet formally been recognised as a refugee.

The word “refugee” is sometimes reserved for successful asylum seekers, meaning those who have achieved formal recognition as a refugee. But that isn’t the whole story. There is nothing in the Refugee Convention stating that a refugee is a person who has been formally recognised by a state or even by UNHCR as a refugee. The whole idea of a ‘”recognised refugee” or of “refugee status” is completely absent from the Convention, in fact. As soon as a person meets the definition at Article 1A(2) of the Refugee Convention — that they have a well-founded fear of being persecuted and so on — that person is a refugee.

So, a formal recognition by a state or UNHCR that a person is a refugee and a formal grand of “refugee status” merely declares something that was already true: that the person is a refugee because they already meet the definition of a refugee. For this reason, lawyers say that refugee status is declaratory.

An asylum seeker may be a refugee. Given the incredibly high success rates for asylum seekers of certain nationalities — Syrians, Eritreans, Sudanese, Afghans and Iranians for example — it seems entirely appropriate to refer to them as refugees even if they have not yet been formally recognised as such.

What is the difference between a refugee and an economic migrant?

Some people set great store by the difference between refugees and economic migrants. A refugee is a person who flees persecution, they say, and an economic migrant is someone seeking a better life. UNHCR have historically drawn a sharp distinction between the two concepts. This is sometimes referred to in academic circles as the refugee/migrant binary: the idea that you can be a refugee or you can be a migrant but you cannot be both.

The problem is that there is no sharp divide. Rebecca Hamlin has written a whole book about this, which I highly recommend: Crossing: How We Label and React to People on the Move.

There is nothing in the Refugee Convention which excludes from refugee status a person who also, as well as having a well-founded fear of being persecuted and so on, also wishes for a better life. If you were fleeing from Afghanistan, Eritrea, Syria, Ukraine or elsewhere, wouldn’t you want to settle somewhere that is not only safe but also where you can rebuild your life, get a job and be joined by your family? This is one of the many reasons it is cruel and inhumane to remove refugees to Rwanda. The prospects for building a new life for oneself and one’s family in Rwanda are much, much worse than in the United Kingdom.

A lot of refugees flee to adjacent countries and stay in refugee camps. Some hope to return across the border. Others lack the wherewithal to move on. But some do move on. That does not cause them to stop being refugees. Many refugees are also, simultaneously economic migrants. And there is nothing wrong with that.

It is also true that many economic migrants are not refugees. If we imagine a Venn diagram, the circle of refugees would largely fall within the far, far larger circle of economic migrants.

So, that’s the legal definition of what “refugee” means according to the Refugee Convention and how the convention is interpreted today. Personally, I think it is fine for people to use the word more widely when referring to victims of flood, famine or other natural disasters. They will be seeking refuge, after all. But for lawyers, the word “refugee” has a very specific meaning and applies to a much narrow group of people.

This article was updated by Sonia Lenegan in June 2024.

[ad_2]

Source link

Related posts: